Dr. Alex Parker

Professor, Oceanography

Miranda Galang, Trip Assistant

California State University, Maritime Academy

May 8-28, 2023

The theme of our trip is the sustainability of marine ecosystems in the face of growing anthropogenic pressures, both locally and globally, due to climate change. The culture and economy of the Bay Islands, Honduras is deeply connected to the Meso-American Reef, and yet, its function and resilience is far from certain. As we learn about tropical marine ecology and interact with Bay Island residents, we will ask questions like, “What changes to the reef have occurred during a single generation? How have these changes impacted lives and livelihoods? What interventions are necessary and practical in order to maintain a sustainable ecosystem? Is there the will to enact these changes and what challenges stand in the way?”

LATEST STORIES

Tuesday, May 23

Joshua Mihalczo

Junior, GSMA

Hello again everyone!

My fellow cadet and friend James McNally and I were tasked to conduct a scientific experiment about the Four-Eyed Butterfly Fish. Not only did we have to conduct the field study, but we also had to create and present a powerpoint of our findings. Neither James nor I had conducted scientific research, so we learned everything on the go. We had eight snorkeling sessions to observe the eating habits of the Butterflyfish for our data, and it exhausted us. Gathering data, inputting the data into Excel to conduct statistics, then putting the information into a Powerpoint was no easy feat. The number of naps we took to maintain motivation was absolutely necessary. Further, the wifi at the resort constantly stopped working and caused us major stress as we tried to complete the presentation on time.

We were so frustrated that we decided to attend a fiesta and drank a delicious virgin piña colada. After the fiesta, we went back to our studies, but the wifi was still refusing to work, so we went to bed and hoped that the next day would be much more productive.

We started the next morning with 200 push-ups to fully wake up, had breakfast with the IE group, and were ready to finish our presentation. Again, the wifi was our enemy. Finishing our presenation should have taken a couple of hours, but instead took most of the day, right up until we had to present our findings to the IE group. Before the final presenation, Dr. Parker wanted every group to do a practice presenation with him. However, we were not fully ready, and the practice went terribly. Dr. Parker, however was very supportive and gave us great advice on how to finalize the presentation. However, his critiques resulted with us recreating most of our presentation slides. To ease our stress, we went to lunch and had some amazing ice cream. Refreshed from lunch, every group presented their findings. James and I were second to last to present. We were editing our presentation up to the minute before we presented. Our presentation went amazing! Our stress was finally gone.

Is is now the end of our International Experience trip, and I have loved every minute of it. Even homework was fun; I promise, I’m not lying. I made some awesome friends throughout this trip, especially James McNally.

In conclusion, this experience has been excellent. Thank you Dr. Parker and Miranda for giving me such an amazing experience here. I would also like to thank all of my friends I made on this trip. Finally, thank you, Jen Keck, and all the staff members that I met at Anthony’s Key Resort. #jesusisking#almostdrownedinacave#loveyall

Tuesday, May 23

Morgan Illman

Junior Oceanography

Hello, everyone! It’s Morgan Illman again. We are beginning to wrap up our International Experience here at Anthony’s Key Resort. It has been a joy to dive around the reef and explore the island. Along with observing culture and getting to know people who live on the island, we are also gaining skills to grow as scientists. Part of our educational experience as oceanography majors is to research the marine ecology of the Roatan coral reef. For the past few days, we have been conducting research projects using field methods that the Roatan Institute for Marine Sciences educator, Jen, has taught us through multiple lectures. Today marks the final day of data collection, and after assessing the data, we will present our findings to our whole group and some guests of RIMS.

The research group consists of myself and fellow cadets Roxanne Mina and Justin Pham. Since we are all certified in open-water scuba diving, we decided to investigate the presence of harmful algae located inside the Roatan Marine Park and compare it to diving sites outside the park.

Brown algae is harmful because it creates a soft, fleshy surface in the coral reef, which new corals cannot attach to and grow. Green algae is also harmful because it is an indicator of potential excessive nutrient runoff from agricultural operations. This type of algae can out-compete corals for space on the reef. We hypothesize that there will be more brown and green algae outside of the marine park because there are fewer protections in place in these areas. To test our hypothesis, each dive session we dove to a depth of about 40-50 feet and placed a square meter quadrat on three different coral locations.

We then took a picture of the quadrat using a GoPro, then recorded the abundance of algae species within each square of the quadrat. This method was tedious underwater because we had to worry about controlling our buoyancy, carrying the necessary supplies, and keeping track of each other, all while trying to record our data.

Despite the challenges, we were able to gather all the data we needed while viewing some awesome marine life.

Thursday, May 25

Matt Rothschild

Junior, Oceanography

As the trip comes to a close, I look back on the wealth of experiences I have gained. One of the most critical experiences was every underwater session, which was almost 18 hours of scuba diving. To end on a high note, the last eight sessions underwater were to conduct a research project that my partner and I will present to my fellow cadets.

Outside of the water, my interview project with Mickey Charteris, the author of Caribbean Reef Life, left a strong impression about how important marine life is to the island of Roatan. Mickey’s work has inspired me to practice underwater photography. Mickey was a great example of how friendly the people of Roatan can be. He not only was open to speak with me about his experiences as a marine photography, but offered me an underwater photography class when I come back to Roatan.

After spending nearly a full month at Roatan, I have learned about marine and coral reef conservation and how challenging ocean conservation is without the support of local organizations such as the Roatan Marine Park (RMP). There seems to be little incentive for governments to take the lead on marine conservation. For example, RIMS Education and Research Coordinator Jen Keck explained that dive resorts like Anthony’s Key cannot charge divers a fee towards the Roatan Marine Park to fund marine conservation because the Honduras government views the fee as a tax towards the mainland. Therefore, any funds generated would not be used towards the island reef. This challenge emphasizes the need for divers and tourists that visit the island to feel empowered to donate to organizations like RMP.

Although much of our trip was spent at Anthony’s Key Resort, we visited various locations in Roatan with a tour guide. However, our group visited the small town of West End twice without a tour guide, and we had the freedom to explore the town independently. Each visit to West End resulted in the most culture shock, since multiple store clerks did not speak fluent English, and the currency exchange was convoluted. I learned just how powerful USD is, because the stores preferred that I paid in USD over the local currency, the Lempira. For example, I went to an ATM to receive Lempira in preparation to purchase goods at West End stores; however, when I was about to pay a clerk in Lempira, they noticed that I had USD in my wallet. They then exchanged the purchase price into USD, and I paid with USD instead. Even walking through West End, local kids running to the store to buy a soda or something else were carrying USD.

In a culmination of all these experiences at Roatan, IE has inspired me to travel more throughout the world to explore new cultures. The next place I would love to visit is the Philippines. I have heard nothing but great things about the diving, and the culture is unique in its own right.

Monday, May 22

Justin Pham

Senior, Oceanography

After being on the island for over two and a half weeks, we are near the end of the IE trip. This trip has given me the opportunity to learn about others and myself. This includes learning about different people’s perspectives on the island, interacting with local islanders, and diving to conduct underwater research projects. By doing so, these factors give me a better understanding of why Roatan is such a special place to tourists, islanders, and mainlanders that come to visit the island. Near the end of our trip, Dr. Parker assigned us to conduct research dependent on snorkelers and diver groups. Each group will perform field surveys of fish, coral, or algae. As the diver group, I have worked alongside fellow cadets Roxanne Mina, and Morgan Illman. Our project objective is to determine the three types of algae—Brown, Green, and Red–which are abundant in the coral reefs at a certain depth below the surface. Our question: how does the algae impact the coral reefs inside the Roatan Marine Park and outside the Marine Park?

For context, we learned that there is a symbiotic relationship between algae and coral, which assists with the health and overall function of the coral reef marine ecology. Many invertebrate species depend on the growth of algae as it is their primary feeding source. Without the invertebrates feeding on the algae that grow on the coral, algae can overgrow, harming coral reefs and the many other marine species that depend on them. Performing transect lines and quadrats at each location is essential to identify the abundance of marine algae. Without monitoring the algae, other algae may potentially overpower coral, resulting in coral succumbing to disease and loss of food for invertebrates.

With the guidance of Educational and Research Coordinator Jen Keck at RIMS and Dr. Parker, we measured the length of a transect line at 40 meters below the surface and placed a quadrat at specific points of the transect. The quadrat was gently laid on top of various coral. The three quadrat locations were placed at 5m, 10m, and 15m of the transect line. Since we are a team of three, one person would lay down the transect line, the other would record the depth, and the last person would take pictures for when we need to analyze the organisms in the quadrat.

Based on our experiments across four days and eight dives in total, we observed that there are more green and brown algae on corals than red algae. There may be a variety of factors as to why this phenomenon is happening. Potential reasons are that the species may rely on certain algae; some algae may be more harmful to environmental conditions; and that the location of the coral reefs inside and outside of the marine park affect which species grow where.

Although placing quadrats along the coral reefs and placing a transect line over several times is daunting, we were lucky to see intriguing animal species that roam the areas, such as sea turtles and French Angelfish.

Sunday, May 21

Atticus Hart

Junior, GSMA

We are two weeks into our stay in Roatan, and we have just begun preparing for our research projects. We were split into two groups and were able to pick our own research idea and learn how to gather the data, culminating in presenting our findings to an audience on Thursday, May 25. My partner and I are looking into the differences of herbivorous fish populations inside and outside of the Marine Protected Area (MPA), off the coast of Roatan. Our focus is on the Stoplight Parrotfish, Rainbow Parrotfish, and other classifications of Parrotfish, along with Surgeon Fish and Blue Tang fish.

The chosen fish species eat algae from hard coral, such as brain coral, maze coral, elkhorn coral, etc. A focus of the MPA is to protect the health and growth of hard coral. Our hypothesis is to know whether the MPA protected coral provides an abundance of algae, therefore, would increase the population of Parrotfish and Blue Tang inside the MPA rather than outside of the protected area.

We are using the “Roving Diver” collection method, which consists of a pair or more individual divers (or, in our case, snorkelers) spreading out in a search pattern to collect data (in our case, fish populations). One challenge of this method is the current of the ocean thwarting our direction to swim in a straight line and our keeping an equal distance apart. To reserve our energy, we begin each survey by swimming into the current for the first half, then swim with the current in the second half. To maintain an equal distance from each other, we regularly lift our heads above the water to accurately view our distance apart and to communicate when we need to switch directions.

Data collection has been interesting, as I have been brushing the cobwebs off the scientific research skills I haven’t used since high school. Our primary challenges are implementing the method, collecting data, and utilizing Excel to aggregate our data. Further, neither me nor my partner are entirely proficient in Excel, for which the presentation requires numerous graphs. To resolve this problem, we plan to take advantage of Dr. Parker’s technical acumen, as well as YouTube videos which have proven invaluable. As we expect more challenges to arise through data collection at various snorkeling sites and in creating the presentation, I am quite confident in our abilities to overcome these issues with Dr. Parker’s guidance and some creative problem-solving.

Saturday, May 20

Erika Tam

Junior, Oceanography

Today we had our dolphin encounter. We received an educational exposition from a dolphin trainer and a performance from one of the nine dolphins. After the presentation, our group snorkeled with the whole dolphin pod. Rather than think about the program as a captive dolphin program, think about it as a case study, an opportunity for people who might study communication to conduct experiments. Dolphin communication is a field of study!

Communication comes in so many different formats; the most common form of communication is language–talking. However, there is no way for any human to talk underwater. Instead, we use signs and focus on body language to convey our message to our dive buddies. Dolphins are experts with underwater communication. With their clicking, jaw claps, and raking, dolphins have many ways to express their emotions to each other. Further, dolphins use echolocation to detect things underwater. They do not have a sense of smell; therefore, they resort to other senses to find their way around the ocean. As we learned during the encounter, they are a playful species; even these animals have feelings that affect their interactions with humans.

RIMS allows these bottlenose dolphins to swim in the open water. They swim outside their enclosure, and choose to come back on their own. After all, why bite the hand that feeds you? If the dolphins come back after spending time in the open ocean, it implies that RIMS is doing something right.

Personally, I feel like the RIMS dolphin encounter program is a balance between the program at San Diego Sea World, where you can stand the entire time in shallow water during the encounter, and the Dolphin Encounter in the Bahamas, where it is an enclosure in open ocean, 20 feet down.

These coastal bottlenose dolphins have learned tricks and interactions with their trainers. One thing the trainers repeated was that if the dolphins choose not to have a good day, the trainers do not force them to behave or do a certain trick if they don’t want to. There is no withholding food for “bad behavior” or mistreatment of any kind. If anything, RIMS has set a reasonable standard: a balance.

In the open ocean, one should not approach these animals and expect the same response as their counterparts in captivity. However, this is as close to an encounter that can be safe for both the dolphins and humans, should everyone and every dolphin follow the rules.

When we snorkeled with the dolphins, I was surprised that the visibility was low: roughly eight to ten feet. Because we have been spoiled with so much visibility during our own dives, it caught me by surprise. Within the enclosure, if the dolphins did not want to be seen, they were not going to show themselves. The coloration of their skin allowed for them to almost blend into the water. With their light underbelly, if you were to look up at them, you would not see them. A very curious and intuitive species, they were playing with the trainer, trying to pop the bubble rings he was blowing. Their conversations underwater were a unique sound to hear. As the dolphin trainer said, “Sometimes they are arguing; sometimes they are playing.”

Friday, May 19

Lisa Hamner

Junior, Oceanography

Today, continuing our survey of fish and coral, along with coral restoration efforts on Roatan, we visited the Port of Roatan to learn more about coral transplantation. Port representative Kester Boddin and marine biologist Alonzo Reyes welcomed us and gave a presentation about their coral restoration efforts on the port property. They showed us how they transplanted coral from one place to another, due to the need to fill in the land to expand the port. They showed us images of four structures made of concrete that adhered to coral fragments: a concrete “cake” structure that resembled a sandcastle, a brick shape, a table shape, and a stingray shape. They had labeled each concrete structure with numbered tags that were written in ink, but were also punctured. (This is because the ink will eventually dissipate from the tag. Coral will grow into the tags, but the number will still be seen.) Some coral eventually grew and overtook these large concrete structures; to me, it was an amazing concept. The scientists said they had approximately 70% success in coral growth.

Boddin and Reyes also showed us how they reduced waste by distributing reusable water bottles to the entire port staff, stopped giving out plastic silverware, and began using recyclable containers when serving food to-go to cruise ship tourists.

After the presentation and question/answer session, we quickly changed into our swimsuits and snorkel gear, and Reyes took us on a snorkel tour of the transplantation site itself. The coral site was in shallow water, and I was amazed at the growth of the transplanted coral. There appeared to be success despite possible sediment, discarded trash from cruise ship tourists, fuel runoff in the water from cruise ships entering the port, and potential water contamination. The concrete structures were much larger than I had expected, but the larger, the better, since many of the coral that was transplanted tends to grow quite big. I saw plenty of brain coral, fan coral, and staghorn coral. I spotted plenty of female stoplight parrotfish nibbling on the coral, a couple of super-male stoplight parrotfish, and some banded butterfly fish. I noticed that the fish treated the transplantation area like a naturally created coral bed; their behavior appeared like fish in the Roatan Marine Park. Unfortunately, there was also plenty of algae present at the coral site, and I did not witness the amount of growth claimed by the presentation, but it was still very awe-inspiring.

During our visit, we did not see a cruise ship come in with hundreds of tourists; everything was quiet and closed up. Normally when cruise ship tourists arrive, there are restaurants, shops, and bars open at the port. I’m certain tourists would be receptive to the idea that a coral transplantation site is so close to them. There should be an information center offering a similar type of presentation to the one we were given, educating tourists on these coral transplantation efforts. I see the relationship between the scientists, the port itself and the tourists as being a cooperative and lucrative one. If the port offered coral snorkel tours to the tourists, surely there would be several from the cruise ship interested. Snorkel tours of the coral restoration site would bring in money to the port and raise money for more research and education and coral restoration efforts.

Thursday, May 18

Josh Bennett

Junior, Oceanography

With our last week at Roatan approaching, we have been tasked with creating, implementing, and presenting a research project related to the overall health of the coral reef.

Fellow cadet Matt Rothschild and I are partnering to investigate whether or not the Roatan Marine Park has an influence on the percent cover and species richness of hard corals along a transect line. Hard corals are the corals that build reefs and are responsible for the complex structures and habitat that we see today. We use percent cover instead of number of living coral heads as an estimate of coral health because not all coral heads are completely covered. If a portion of a coral head is covered, it may be considered alive but also be in a state of degradation.

The Bay Islands National Marine Park (BINMP) is an area along the western edge of Roatan which is maintained by the Roatan Marine Park (RMP), a non-profit organization that works to protect local reefs from mechanical damage and overfishing, and ensures that environmental laws are enforced. Of the sites that we are going to be diving in the next week, half will be within the marine park and half will be outside of the marine park. This will provide us an opportunity to study whether the actions taken by the RMP are having the intended effect and to understand how the corals outside of the BINMP are faring. Due to the goals of the RMP, Matt and I expect that there will be a higher percentage of hard coral cover at sites within the BINMP and that the sites outside of the BINMP will have less coverage.

We are going to be taking a 30 meter transect line along a flat portion of the reef and placing five, one-meter squared quadrants at random spots along the transect line. Once the quadrant is aligned with the randomly generated point along the transect, we take a picture of the quadrant and conduct a visual estimate survey of what species of corals are within our quadrant and what percent of the area of the quadrant is occupied by hard corals. Once we have this information, we can compare percentage cover values between sites and determine which areas have greater percentage hard coral cover.

Wednesday, May 17

Austin Sargent

Junior, Oceanography

We are nearing our second week at Anthony’s Key Resort in Roatan, Honduras. Today, we examined projects and companies focused on coral reef restoration in Roatan.

In the morning, we began with a lecture about the health of the local coral populations of Roatan. We learned which species of coral play a significant role in the reef’s health and why there has been such a massive decline in the coral reef in recent decades. Between human activity and diseases, the local coral population couldn’t keep up: it suffered and fell into a state of decay. In addition to the lectures, we also received hands-on experience in coral restoration. Our boat captain drove us to the coral trees near Anthony’s Key, and the scuba divers and snorkelers had separate goals to accomplish with restoration. The scuba divers followed education coordinator Jen down to the trees to hang new pieces of elkhorn coral, then clean the overgrown algae off the branches of the coral trees.

The coral trees were suspended in the open ocean and tied to the bottom with weight and rope, creating a coral tree nursery in which many stocks of coral could be found. The coral that was chosen to be hung was a new genotype of elkhorn that had not been hung anywhere else in the coral nursery. New genotypes are constantly sought after to fragment and hang in the coral trees of the nursery, as the new genotypes are advantageous. The new genotypes will increase the genetic diversity of the coral species allowing coral populations to better survive against any possible outbreak or changes in the area that they will be outplanted. As recently as three years ago, a coral disease wiped out most of the coral populations found in Roatan, leaving a coral-absent wasteland in its wake. Elkhorn coral was chosen to be fragmented as they provide many benefits and advantages regarding the future of the reef. Additionally, Elkhorn supports the local marine life found on reefs as they offer great hiding spots.

After hanging the coral on the trees, we then proceeded to brush and clean the trees of all algae that had been collected on the branches. The algae will outgrow and outcompete any of the Elkhorn, slowing the coral’s growth. Snorkelers were given the job scrub the algae off the buoys that helped suspend the trees in the water. Together, we created a new coral tree with a unique Elkhorn genotype and properly cleaned and managed the other coral trees in the nursery.

The importance of the coral reef cannot be understated for Roatan’s survival. Not only is the reef the main source of economy for the nation, but the reef also is a source of food, culture, and a form of security, as it protects the coastlines.

Tuesday, May 16

Roxanne Mina

Junior, Oceanography

Through the Roatan Institute of Marine Sciences (RIMS), we’ve had the opportunity to learn about the island’s history, people, and basic tropical marine ecology. RIMS’s key purpose is “the preservation of natural resources through education and research,” specifically Roatan’s coral reef. Not only do they benefit organisms by acting as a rich habitat, but healthy reefs contribute to human interests by bringing in tourism, contributing to fisheries, and acting as a natural wave breaker for coastal cities. It’s interesting to note that all these benefits are achieved by these animals! Yes, corals are animals! Coral reefs are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, only second to rainforests. In our most recent lecture, we learned about what organisms inhabit Roatan’s coral reef system.

Invertebrates are animals that lack a spine, and 95% of all known species belong to this group. The phyla seen in Roatan are Porifera, Cnideria, Ctenophora, Annelida, Mollusca, Echinoderma, and Arthropoda, and some representatives are sponges, coral, comb jellies, fire worms, starfish, and crabs, respectively. Until now, we have focused on coral: their importance, future, and the conservation and restoration projects that come with the issues they face. Since our invertebrate lecture, I’ve been interested in learning more about the phylum Mollusca, including snails, bivalves, nudibranchs, squid, and octopus. These organisms are distinguished by their soft bodies and may have the ability to produce a shell.

The species I’m most interested in learning more about is the mollusk, Octopus briareus, also known as the Caribbean Reef Octopus. While other mollusks, like conch or chiton, carry a shell, the octopus is completely soft-bodied, aside from their beak. An interesting fact is that an octopus is able to go through any crack or crevice, so long as their beak can fit through it. Not only that, but the Caribbean Reef Octopus has the ability to change the color of its skin through the presence of chromatophores, and its color ranges from green to bluish and speckled with brown. It feeds by covering an entire rock and sweeping a tentacle under the rock to capture any prey underneath. This was a behavior that I was able to witness during my first night dive. Since then, I’ve been able to see four octopuses! As I continue to dive, I hope to also be able to find and recognize more of invertebrate life.

Monday, May 15

Matt Rothschild

Junior, Oceanography

Today felt longer than other days because we spent most of it visiting a nearby key. Exploring Maya Key offered us a new educational experience to learn about the indigenous land animals and take a tour of Mayan ruins. For our first dive of the day, we explored a fringing reef off of a major cruise port. When we finished, we then traveled to Maya’s Key for lunch and to explore. The first building we saw at Maya’s Key was a souvenir shop, signaling that the Key catered to cruise tourists. After lunch, we had an hour and a half to explore the Key before joining together.

During our break, we went on a tour of the Mayan ruins. The ruins were not authentic; they were buildings that resembled what ruins would have looked like on the Key. Inside the ruins was a museum of Mayan art, depicting their culture through sports, literature, and food. Our tour guide was deeply passionate about the history of the Mayans and added interesting facts about their culture, which brought a richness to the tour experience.

As we continued with our tour, we were guided to the animal exhibits. The tour guide spoke about the animals, their behaviors, and natural habitats. Surprisingly, the tour guide would get close to their enclosure fences and the animals would approach the guide. The animals seemed to have a connection with the tour guide, going over to be pet. Even when the jaguar snarled at the guide, they did not flinch and described that the animals’ temperament changes are normal. My favorite animals were the monkeys because they became joyous when the guide arrived at their enclosure. They reached their arms out to the guide and the guide held their hands.

At the end of the tour, we walked back to the dive boat. While we rode the boat back to Anthony’s Key, I reflected on the differences between Anthony’s Key and Maya’s Key. Maya’s Key had Anthony’s Key Resort staff working the bar and lunch, but also performing various other duties throughout the island. With Anthony’s Key focusing on reef and marine life, why did Maya’s Key focus on animals and Mayan history? Further, as Maya’s Key is adjacent to a cruise port, why did the owner of Anthony’s Key offer the guests an experience about Mayan history, rather than reef and marine life education? These questions have only broadened my interests.

Sunday, May 14 – Happy Mother’s Day!

James McNally

Junior, IBL

I chose to go to Honduras for my international experience because I thought that I may never have another opportunity to spend three weeks of my life on a tropical island in the Caribbean. Since I was young, I have loved being in the water, specifically the ocean. Sometimes I joke with my friends that if I could choose another career, it would be Marine Archaeology. I was not sure what to expect coming to Roatan, but so far, I have not been disappointed!

We have spent an entire week here, and everyone in our group has become used to island life, whether it’s the feeling of ocean water drying on our skin and clothes or of being extremely tired or ravishingly hungry at random moments throughout the day. We re-wear the same clothes for multiple days and our clothes never feel fully clean. The lifestyle of visiting a tropical island for multiple weeks has an adjustment period, but I think that most of the group has acclimated well to the dive resort culture.

Aside from diving and living on the island, we are also learning about the reef and its livelihood. Interesting topics such as ocean life and land development have been taught through lectures and research paper discussions. Other than coral, fish, and turtles, we have had in-depth discussions about the emerging threats and changes to the reef around Roatan. Many threats are considered “anthropogenic” factors, meaning they are caused by humans. One example of this is sediment debris polluting the reef, due to recent construction of the main highway in Roatan. Since the ground here is largely composed of fine red clay particles, in the rainy season the fine particulates of the clay that are not filtered through the mangrove trees eventually float to the coral reef, causing the coral unnecessary stress. This is just one of many examples of how coral reef health is threatened.

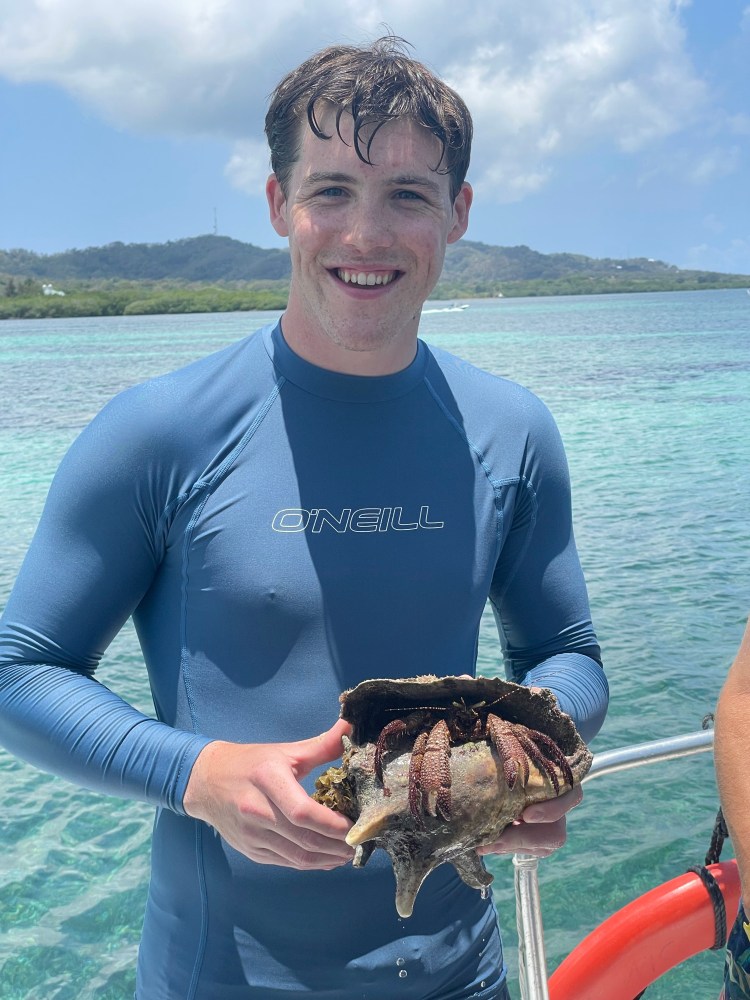

Outside of our classes and discussions I have enjoyed leisure time and have been building great relationships with my group. Specifically, I have become close friends with my roommate and fellow Cal Maritime cadet, Josh Mihalczo. It did not take long for a bond to develop between us when we had to battle the cockroaches in our room together. Each night before we head to bed, we walk around Anthony’s Key and try to find cool wildlife. This includes land and ocean dwelling creatures, such as lionfish, iguanas, octopus, hermit crabs, and cats. Each night that we have explored, two cats have joined in our adventures. We have named one cat “Prissy,” short for Priscilla, and the other named “Coal,” short for Charcoal. While we were searching for iguanas and hermit crabs, the cats followed us and hunted for lizards. I guess you could say that we are more than comfortable living in our new island lives.

With only a week and a half left of our International Experience here in Roatan, I am continuously looking forward to our lectures, learning about the reef, and the diverse culture that the island of Roatan has to offer. I hope the days don’t start going by too fast, because I am really starting to like this place!

#roachhunting #pineappleupsidedowncake #mangoicecream #islandlife #savethereefs #yolo

Saturday, May 13

Joshua Mihalczo

Junior, GSMA

I came to Honduras because I often swim in the ocean during work breaks in my hometown, and I enjoy being around marine life. Today we explored both the mountains and ocean of Roatan. We began at a rainforest and learned about many species of plants and animals both native and invasive to the island, then snorkaled in a shallow area of Anthony’s Key.

In the morning, we visited a rainforest called the Carambola Gardens. The gardens are owned by a man named Bill, and he was our tour guide who showed us the various plants that grow in Roatan. Bill told us that many plants were in season, such as mangoes, papayas, and other blooming fruit. Bill told us that Meso-America was where chocolate originated, and that the Mayan people invented the method to ferment the cocoa pods that eventually would turn into chocolate. After Bill finished speaking to us about the various plant life, he introduced us to our guide, Johnny, who led us to the top of the mountain. Johnny did not speak any English, but knew the land very well. As we were hiking through the rainforest we were able to identify many plants that Bill had taught us. We also saw huge, poisonous spiders as big as our hands. Near the top of the mountain, we were able to view the reef and see Anthony’s Key.

After our experience through the rainforest, we had the afternoon to ourselves. A few classmates left the resort to explore a busy area on Roatan called the West End. Myself and a fellow classmate, James, decided to stay at the resort. We first relaxed by the pool, played a popular ring on a string game, and got to know the pool bartender. When it was time for lunch, we were making our way towards the restaurant, when we saw a massive iguana of about five feet in length, swimming in the ocean. The nature at Roatan is vast and we are always seeing animals or fish. After lunch, we borrowed a scythe to cut down coconuts from trees and we ripped open the husk to eat them. Exploring what nature offers with food or plant life has been an enjoyable experience.

When my classmates arrived back from West End, we all went to the shore dive to to snorkel. The shore dive is a section of Anthony’s Key that has open, shallow water to explore the marine life just next to our bungalows. The water there is beautiful and crystal clear. While the group went out far into the water, I stayed close to the shore to look for queen conch, a very large animal that is a member of the snail family. Utilizing my knowledge about the conch, I swam to a grassy, algae-covered ocean floor where conch are usually located. After a few minutes of searching, I found a queen conch that was awake and I was able to see its long eyes. I could not tell where it was staring. After observing the queen conch, I decided to find where my classmates were swimming. As I was swimming towards them, I stumbled upon a lionfish, which is an invasive species. The lionfish is a dangerous species to the reef because it eats small reef fish, which are vital to the survival of reefs. Lionfish cause a lot of devastation and are spreading around the world and overpopulating. I also found a scorpionfish, which happens to be related to the lionfish, but is not invasive to the reef. It is interesting that related fish can have different impacts on the reef.

The island of Roatan is absolutely beautiful, and the opportunity to visit the island is amazing. After learning about the many species of wildlife in both the rainforest and the reef, I have fallen in love with this place. I highly recommend visiting Honduras and staying here at Anthony’s Key Resort.

Thursday, May 11

Atticus Hart

Junior, GSMA

During the last three days, we have learned about the various components of coral reef ecosystems off Roatan, Honduras. Through what we have learned and observed, many comparisons can be drawn between the ecosystems of the coral reefs of Roatan and the human ecosystems in which we live. On the first day of our trip, our morning lecture was a brief introduction to coral reef ecosystems and their importance to the island of Roatan and the world. A key emphasis of this lecture was the diversity, interconnectedness, and interdependency of the reef ecosystem and how the various components work together to form a thriving and incredibly diverse ecosystem. The human ecosystem has many parallels. We are a wide range of people with varying roles and responsibilities. When we perform those roles as a society or ecosystem, it makes the world a more secure and prosperous place, much in the same way that the various parts of the coral ecosystems ensure their prosperity and survival through cooperation and filling their role.

As we continued to learned about the components of the reef ecosystems during days two and three, it became more apparent that if one system in the reef fails to accomplish its task or is eliminated by some factor, whether that be climate change, predation by invasive species or disease, the ecosystem becomes less diverse, less prosperous and its security is compromised. For example, if the coral cannot photosynthesize, the coral will expel symbiotic algae, which can lead to coral bleaching; a slow death of the coral.

This phenomenon of interdependence can be echoed in the human ecosystem. If an essential working group, take plumbers for example, were to stop being able to do their jobs, the luxuries like running water and municipal plumbing that we take for granted would cease to exist, severely impacting the quality of life of the human species. Just like the algae not being able to do their jobs does for the coral.

We also recently discussed the anthropogenic impacts that can be seen on coral. The Anthropocene is the period in which humans have been the dominant driving force of natural changes on the planet, and since this began, we have been able to see significant effects on coral reef ecosystems. Anthropogenic effects like overfishing, pollution, climate change, and development all have negative effects on coral ecosystems. These anthropogenic effects are also felt by human beings. Overfishing leads to a scarcity of fish, which directly affects all coastal communities that depend on the sea as a key food source. Pollution has a direct impact on the quality of water used and consumed by human beings, and climate change has caused tangible adverse and extreme weather conditions, like California’s longer and more devastating wildfire seasons and droughts.

While it seems like coral ecosystems and human ecosystems portray many of the same negative parallels, they also share some positives. The most prominent of these that we have discussed is resilience. While both the coral and human ecosystems are sensitive and fragile, both have a key component of resilience. Coral reef ecosystems can bounce back from disease, bleaching events, and other environmental stresses. Just as the human ecosystem can bounce back from adverse events like disease, storms, and natural disasters. Similar to the coral reef ecosystems, the human ecosystem bounces back by relying on factors like diversity, interconnectedness, and being dependent on its various components. Without all of us, we are weaker and cannot adapt to the ever-changing world in which we live in. This is something we can all benefit from being reminded of from time to time.

Wednesday, May 10

Justin Pham

Senior, Oceanography

We are on the Bay Islands in Honduras; specifically, Roatan in Central America. While here, , I will be conducting research on Tropical Reef Ecology. Experiencing the hot and humid climate as we arrived in Roatan was a complete shock after having just left the chilly Bay Area of California.

For the past two days in Roatan, I have experienced many aspects of Anthony’s Key Resort. So far, I am enjoying observing ancient coral reefs surrounding the island, learning about the importance of Bottlenose Dolphins, and scuba diving down to 60ft. Anthony’s Key Resort is a significant resource to both the Roatan island and the coral reef. Jen Keck, the Roatan Institute for Marine Science (RIMS) education coordinator, oversees and directs the next generation of students to learn how the Bay Islands play an active role in the Meso-American coral reefs. We had a lecture today on how to identify different types of corals and their impact on the marine ecosystem. To reinforce our knowledge of coral identification, we went to the wet lab to name various species of corals by observing and comparing the skeleton of the coral to the picture of the coral. Mustard Hill, Finger, and Staghorn corals are a few species we had to identify. Identifying the names of each coral was easy due to physically holding the skeletons close and utilizing a magnifying glass to view the intricate features of each coral.

The Bay Islands consist of around 70 species of coral. We were tasked to identify only twelve species of coral during today’s morning and afternoon scuba sessions. Half of the students scuba dived to corals closely but at deeper depths, and the other half of the students snorkeled and identified the coral in shallow areas. Identifying the types of coral species can be difficult because many species are similar in shape, size, and color. Each coral’s distinctive features are an integral part of maintaining the biodiversity and marine ecosystem. Learning about coral identification in the classroom is vastly different from learning about corals while underwater.

Monday, May 9

Erika Tam

Junior, Oceanography

Here, we have over 20 dives scheduled, and today was the beginning of our 19-day trip here at Anthony’s Key Resort (AKR). We began with an introductory lecture about the corals we would see here in the Meso-American reefs and the AKR’s backyard. The fringing reefs that we can see with our eyes on the surface are not the same until we look with our eyes and go underwater.

Turn off the music, and turn up your ears. If you listen closely, you can hear the birds chirping, the wind blowing past, the waves hitting the mangrove trees, and the waves as they hit the soft sand beach. The ripping, but soft sound is enough to put the mind at ease.

Inhale. Exhale. Silence. Inhale. Exhale. Silence. See the bubbles rise to the surface.

This is all you can hear when you are below the surface level. A beautiful universe exists beath the waves. So many colors exist—the blues, purples, bright reds and yellows–and litter the sea floor. The reef fish themselves show off their colorful scales. The coral reefs themselves here in the Meso-American reef have many bright colors. Almost every color one looks for in a rainbow exists beneath the waves, like beautiful fan coral that sways with the ocean current, and brain coral bigger than a person’s wingspan.

These animals have existed before us and hopefully will exist long after you and I have passed. The sad reality is that even people here can see the reefs dying, their skeletons littered on the ocean floor. The dead coral can no longer display their shining colors. To determine the overall health of a coral reef, one must consider the mortality index, water quality, and biodiversity. If the water is too cold or too warm, corals will go through coral bleaching, leaving their exoskeletons behind. Since reefs are the most biodiverse parts of the oceans, it is important to consider the animals around the reefs. It is crucial to pay attention to corals’ size, bleaching status, and extent of morality from predation or disease. There is more than one way for corals to die, and different abiotic factors determine their health.

The Meso-American reef is the second-largest system in the world. It is imperative to do anything to prevent or slow down the loss of the coral ecosystem. Humanity will suffer the consequences if the world’s oceans lose their already small coral ecosystem.

Let the oxygen in your body do the work for you as you move up and down with the ocean currents. Use your eyes. Look at the color and be a willing visitor to the world that is the ocean.

Sunday, May 8

Lisa Hamner

Junior, Oceanography

Travel day to Roatan from San Francisco Airport. All taking part can agree: it was a looooooonnng day. Thirteen of us intrepid travelers boarded the redeye flight to Houston, Texas and then, after a short layover, we flew to the Island of Roatan in Honduras. All combined, it was approximately 9-10 hours of travel which went off with pretty much without a hitch. I was amazed, as I’m used to hectic travel and things going wrong in transit. Dr. Chisholm had come to San Francisco airport to see us all off. Dr. Parker’s young son helped him haul in a box of textbooks into the airport. As soon as the son got a kiss goodbye from Dr. Parker, it hit me: we were really going to Roatan after months of anticipation.

I was struck by the welcoming and relaxed nature of the islanders. I wonder if perhaps in the Bay Area we are doing things wrong, because everybody is in a hurry there. Not here in Roatan! As soon as we landed, I noticed the difference. A contingent of runway agents in yellow vests was ready to meet us as we descended the staircase when we came off the plane. I noticed the friendliness of the immigration and customs officials as they checked over our passports and scanned our fingerprints. We were welcomed by the resort representatives, who drove us in an air-conditioned bus to Anthony’s Key Resort. I noticed the distinct Central American themes that I had only previously seen on TV or films: boys riding dirt bikes everywhere, an abundance of palm trees, tin roofs on homes, the humidity, and the heat.

I love the melding of the Caribbean and Latin American, which manifests in the food, the language, the accents, and the attitudes. I can understand Mexican Spanish well enough; however, with Honduran Spanish, due to the dialect difference, I can only catch every other word. The Hondurans can understand my Mexican Spanish, however, so it’s all good. I’ve made friends with Timmy, the guy working the pool bar, and he told me (when I mentioned I must open my laptop and do some writing), “Some vacation you are having, my dear! You need to come back here when you can lay by the pool and relax!” I like the vibe of the pool crowd. It’s mostly middle-aged or elderly folks, maybe a couple of younger newlyweds on vacation, but the vibe is so chill and welcoming.

The Roatan Institute for Marine Science is where we will attend our lectures for the next three weeks. The building was once a nightclub, and I can see the vestiges of its former use. Jen Keck, the resident scientist, is awesome, and I look forward to learning more about tropical coral reefs with her. I also look forward to snorkeling to see the coral in situ.

I was also struck by how much the island resembles Disneyland or the Los Angeles Zoo. Then I remembered that the coral reef at Disneyland and the tropical environment at the zoo are modeled upon this environment. This is real, Disney is fake.

Another new pool friend I’ve met here has just told me to get off my laptop and enjoy myself and jump into the pool. Soon, my new Roatan friend, soon.